拍品 3024 - A211 瑞士艺术 - Freitag, 29. November 2024, 02.00 PM

FERDINAND HODLER

(Bern 1853–1918 Geneva)

Lake Geneva with Mont-Blanc in the early morning hours, March. 1918.

Oil on canvas.

Dated and signed below on the right: 1918 F. Hodler.

66 × 80.5 cm.

Provenance:

- Auction Galerie Moos, Geneva, 23.3.1935, Lot 94, as "Le Mont-Blanc".

- Collection Arthur Stoll, Arlesheim, from 1957.

- Heirs of Arthur Stoll estate 1971-1994.

- Auction Galerie Kornfeld, Bern, 24.6.1994, Lot 51, as "Genfersee und Montblanc-Kette vor Sonnenaufgang".

- Prominent Swiss private collection, acquired at the auction above.

Exhibited:

- Likely Basel 1919, Gedächtnisausstellung Ferdinand Hodler, Kunsthalle Basel, 18.5.–22.6.1919, no. 115, as "Le Mont-Blanc, aurore".

- Likely Geneva 1920, Expositions: Joseph Communal. Newell Marshall. A. Sandoz. A. Stockmann. Art ancien. Art moderne, Galerie Moos, November and December 1920, no. 181, as "Le Mont-Blanc au lever du soleil".

- Bern 1921, Hodler-Gedächtnis-Ausstellung, Kunstmuseum Bern, 20.8.–23.10.1921, no. 642, as "Mont Blanc bei aufgehender Sonne".

- Munich 1925, Ferdinand Hodler. Geboren 1853 zu Bern. Gestorben 1918 zu Genf, Moderne Galerie Heinrich Thannhauser, September 1925, no. 67, as "Mont Blanc bei Sonnenaufgang".

- Likely Geneva 1928, Exposition Ferdinand Hodler, Galerie Moos, 15.5.–30.6.1928, no. 81, as "Le Mont-Blanc, Lever du soleil".

- Likely Geneva 1930, Exposition. Les maîtres de la peinture contemporaine, Galerie Moos, May 1930, no. 42, as "Lac et Mont-Blanc, lever du soleil".

- Likely Geneva 1936, Ferdinand Hodler. Exposition organisée à l'occasion du XIVe Congrès international d'Histoire de l'Art, Galerie Moos, 8.9.–6.10.1936, no. 84, as "La chaîne du Mont-Blanc, lever du soleil".

- Geneva 1938, F. Hodler. Exposition commémorative à l'occasion du XXe anniversaire de sa mort, Galerie Moos, 19.5.–19.6.1938, no. 122, as "Le Mont-Blanc au lever du soleil".

- New York 1940, Exhibition of paintings by Ferdinand Hodler 1853-1918, Durand-Ruel Galleries, 13.5.–31.5.1940, no. 10, as "Le Mont-Blanc à l'aurore".

- San Francisco 1940, Paintings by Ferdinand Hodler, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, July and August 1940, no. 10, as "Le Mont-Blanc à l'aurore".

- Geneva 1950, Exposition F. Hodler 1853-1918, Musée de l'Athénée, 8.9.–21.9.1950, no. 56.

- Arlesheim 1953, Kunstwerke aus Arlesheimer Privatbesitz, Kirchgemeindehaus Arlesheim, 13.–28.6.1953, likely no. 5.

- Vienna 1962/63, Ferdinand Hodler. 1853-1918. Organised by Kulturamt der Stadt Wien, Secession, 6.11.1962–6.1.1963, no. 85, as "Genfersee und Montblanc-Kette vor Sonnenaufgang".

- Zurich and Biel 1964, Ferdinand Hodler. Landschaften der Reife und Spätzeit, Kunsthaus Zürich; Städtische Galerie Biel, 22.2.-5.4.1964; 17.4.–24.5.1964, No. 133. (only exhibited in Zurich.)

- Wetzikon, Bülach and Schwamendingen 1970, Ferdinand Hodler-Ausstellung, no. 53.

- Trubschachen 1970, 4. Ausstellung Schweizer Maler Trubschachen. Das Welschland. 25 Künstler mit 160 Bildern aus Museen und Privatbesitz, Turnhalle Trubschachen, 20.6.–12.7.1970, no. 109, as "Genfersee und Mont-Blanc-Kette".

- Trubschachen 1982, 10. Gemäldeausstellung Trubschachen. 22 Künstler mit rund 190 Werken, Kulturverein Trubschachen, 19.6.–11.7.1982, No. 56.

- Berlin, Paris and As 1983, Ferdinand Hodler, Nationalgalerie Berlin; Musée du Petit Palais; Kunsthaus Zürich, 2.3.–24.4.1983; 11.5.–24.7.1983; 19.8.–23.10.1983, No. 217.

- La Tour-de-Peilz 1985, Peintres du Léman, Château, 26.4.–27.5.1985, No. 18, as "Lac Léman avec banc de nuages".

- Trubschachen 1990, 13. Gemäldeausstellung Trubschachen. Wege zur Farbe. Schweizer Maler von der Jahrhundertwende bis heute, Kulturverein Trubschachen, 23.6.–15.7.1990, no. 19.

- Vienna 1992/93, Ferdinand Hodler und Wien, Österreichische Galerie, 21.10.1992–6.1.1993, no. 57.

- Munich and Wuppertal 1999/2000, Ferdinand Hodler, Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung; Von der Heydt-Museum, 25.6.–10.10.1999; 24.10.1999–3.1.2000, no. 100.

- Madrid 2001, Ferdinand Hodler. Fundación "la Caixa", Madrid, 5.10.–25.11.2001, no. 51, as "El lago Léman y el Mont-Blanc al alba".

- Bern and Budapest 2008, Ferdinand Hodler. Eine symbolistische Vision, Kunstmuseum Bern; Museum der Bildenden Künste Budapest, 9.4.–10.8.2008; 7.9.–14.12.2008, No. 159, as "Genfersee mit Mont-Blanc am frühen Morgen, März".

- New York and Riehen 2012/2013, Ferdinand Hodler. View to Infinity, Neue Galerie; Fondation Beyeler, 20.9.2012–7.1.2013; 27.1.–26.5.2013, No. 42, as "Lake Geneva with Mont Blanc, Early Morning, March".

Literature:

- Werner Y. Müller: Die Kunst Ferdinand Hodlers. Gesamtdarstellung. Volume 2. Reife und Spätwerk 1895-1918, Landschaftskatalog, Zurich 1941, no. 619, as "Montblanc bei aufgehender Sonne".

- Werner Y. Müller: The Art of Ferdinand Hodler. Gesamtdarstellung. Volume 2. Reife und Spätwerk 1895-1918. Landscape catalogue, Zurich 1941, p. 301.

- Hugo Wagner: Hodler Ferdinand. Maler. Zeichner. Grafiker. Bildhauer, in: Künstlerlexikon der Schweiz. XX. Jahrhundert, Frauenfeld 1958-1967, vol. I, p. 448, as "Genferseelandschaft".

- Marcel Fischer: Collection Arthur Stoll. Skulpturen und Gemälde des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Zurich 1961, p. 72, no. 409 (with ill.).

- Hans A. Lüthy: Ferdinand Hodler. Sechzehn Bilder aus der Collection Arthur Stoll. Mit einer Einführung von Hans A. Lüthy, Zurich und Stuttgart 1964, no. 15 (with ill.).

- Hansjakob Diggelmann: Die Werke Ferdinand Hodlers in der Collection Arthur Stoll, 1972, p. 129, no. 86 (with ill.).

- Guido Magnaguagno: Landschaften. Ferdinand Hodlers Beitrag zur symbolistischen Landschaftsmalerei, in: Ferdinand Hodler, Zurich 1983, p. 319.

- Dieter Honisch: Das Spätwerk, in: Ferdinand Hodler, Zurich 1983, p. 456.

- Jura Brüschweiler: Ferdinand Hodler (Bern 1853-Geneva 1918). Chronologische Übersicht: Biographie. Werk. Rezensionen, in: Ferdinand Hodler, Zurich 1983, p. 168.

- Felix Baumann: Gedanken zur Farbe, in: Ferdinand Hodler, Zurich 1983, p. 363.

- Cornelia Reiter: Katalog der Gemälde und Zeichnungen, in: Ferdinand Hodler und Wien. Österreichische Galerie Oberes Belvedere Wien, Vienna 1992, p. 222 (with ill.).

- Guido Magnaguagno: Landschaften 1904-1918. Mit Textauszügen von Ferdinand Hodler, Dieter Honisch, Georg Simmel und Willy Burger, in: Ferdinand Hodler und Wien. Österreichische Galerie Oberes Belvedere Wien, Vienna 1992, p. 104.

- Jura Brüschweiler: Ferdinand Hodler. Collection Steiner, Zurich 1997, p. 220 (with ill. no. 76).

- Jura Brüschweiler: Le chant du cygne de Ferdinand Hodler. Essai sur la relation entre oeuvres peintes et témoignages écrits, in: Ferdinand Hodler et Genève. Collection du Musée d'art et d'histoire Genève, p. 91 (with ill. no. 23).

- Bernadette Walter: Biografie, Ostfildern 2008, p. 374.

- Paul Müller: Aspekte der Landschaft im Werk Ferdinand Hodlers, in: Ferdinand Hodler. Eine symbolistische Vision, Ostfildern 2008, p. 262.

- Christian Klemm: Das Licht in der Kunst Ferdinand Hodlers, Ostfildern 2008, p. 336.

- Oskar Bätschmann and Paul Müller: Ferdinand Hodler. Catalogue raisonné der Gemälde, ed. Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft, vol. II, Die Landschaften, Zurich 2012, p. 456, no. 589 (with ill.).

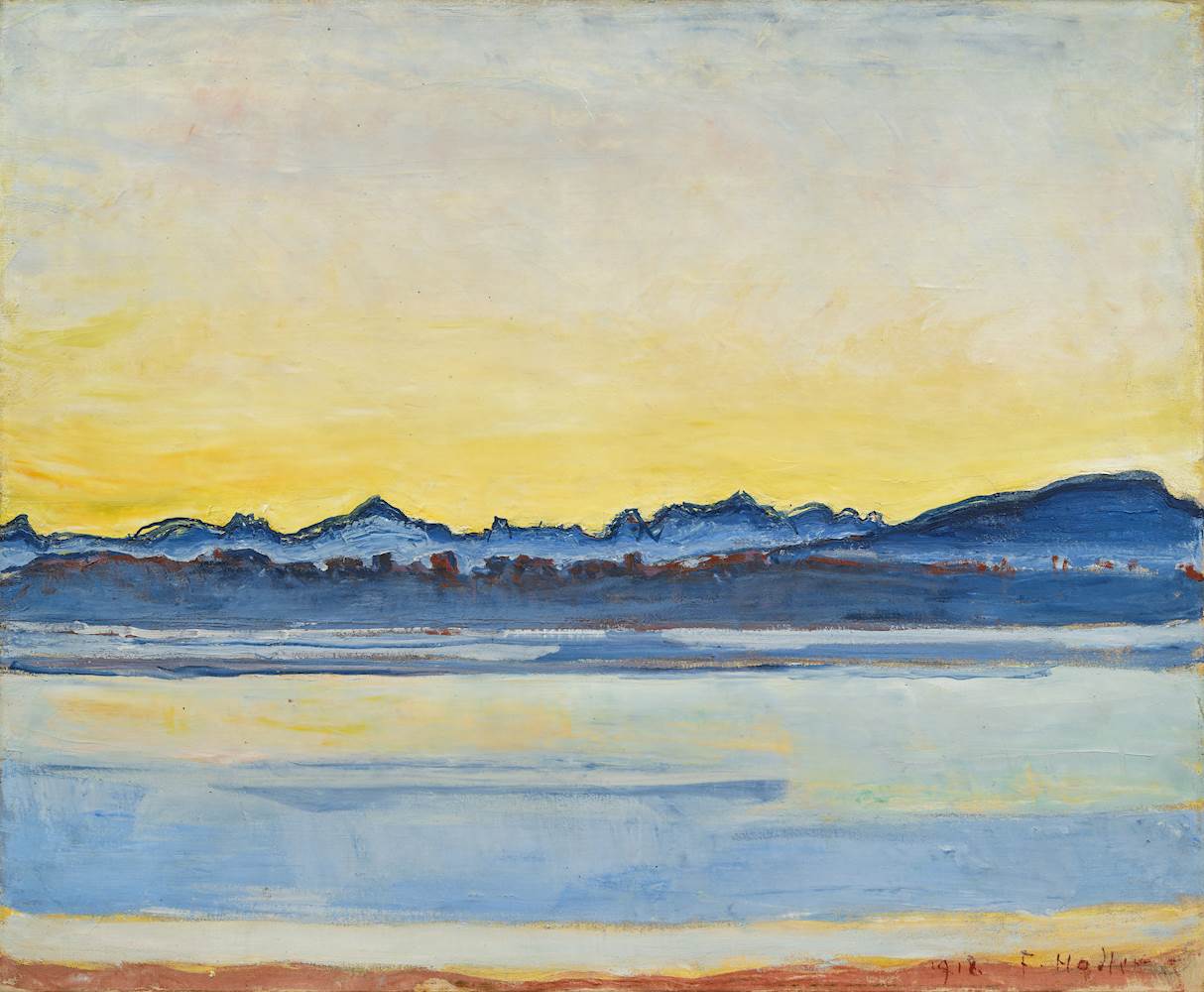

In autumn 1917, due to a lingering bout of pneumonia, Ferdinand Hodler was forced to abandon his poorly heated studio in the Acacias district of Geneva and work from his apartment on the Quai du Mont-Blanc. Hodler’s inconvenience was art history’s gain: a series of impressive views of Lake Geneva with Mont Blanc, painted from Hodler’s apartment, which have become the painter’s artistic legacy. The work to be auctioned is one of this series of eighteen paintings, which were created up until his death in May 1918. Thanks to the catalogue of the retrospective exhibition at the Galerie Moos in Geneva on 11 May 1918 – which Hodler visited shortly before his death – the painting can be dated to March of that year.

Hodler had moved into the apartment at 29 Quai de Mont-Blanc in December 1913. The panorama from there – with the ‘petit lac’ end of Lake Geneva, the Mont Salève and the distant Mont Blanc range – had already been captured by the artist in 1914 in a few paintings, in which the striking horizontal line of the row of houses on the opposite bank is overlapped by the summit of Geneva's ‘local’ mountain and, in some versions, the shoreline is populated by a series of rhythmically grouped swans. In the last series of works, to which this picture belongs, Hodler largely avoided anecdotal details or any references to civilisation.

The view was painted early in the morning before sunrise, as in eleven other versions. The remaining seven works, painted in the afternoon, are dominated by colder shades of blue. The pictorial field of the present view, tuned to a complementary blue-yellow chord, is divided horizontally into several zones, with the line of the mountain range dividing the composition in two. Above the strip of shore, painted in brown and white, the bright blue shades of the lake's surface are awakened by the yellow reflection of the morning light. The opposite bank is marked by a darker strip of trees and houses hidden by the morning fog. Above it extends the mountain range, delineated by the artist with a dark brushstroke, the blue tones of which contrast with the intense yellow of the morning sky. The horizon is marked by the triangle of the Môle mountain on the left, the broad Mont Blanc massif and, on the right, the nearby Petit Salève. Towards the upper edge of the picture, the yellow fades into light pastel shades.

Hodler often used the so-called Dürer disc to precisely transfer the contour of a model and, in isolated cases, of a landscape. Observing the landscape from his apartment, the artist seems to have used the window itself as a kind of Dürer disc, as Johannes Widmer writes: ‘For these pictures, he created diagrams across the entire width of the window of his room, painted in blue and red oil lines, which sharply reproduced the various silhouettes of the lake and mountains. These contours provided the framework for the landscapes, which were painted broadly and fluidly.’ [1]

Repeated forms, symmetries and parallels are compositional devices within Hodler’s theory of ‘parallelism’. According to the artist, they are an expression of the structural laws of nature, to which animate – including human – and inanimate matter are equally subject. Hodler’s view of the tendency of all objects towards the horizontal as a law of nature is also linked to death as human destiny (think, for example, of the series of works featuring the dying Valentine Godé-Darel): ‘Tous les objets ont une tendance à l’horizontale, à s’aplanir sur la terre, comme l’eau, en cherchant une base toujours plus étendue. La montagne s’abaisse, s’arrondit par les siècles jusqu’à ce qu’elle soit plane comme la surface de l’eau. L’eau va de plus en plus vers le centre de la terre, ainsi que tous les corps.’ [2] In this sense, Hodler’s last paintings are not mere snippets of a specific landscape, but represent allegorically a timeless law of nature.

The large symbolist figure paintings and portrait commissions of recent years had demanded a great deal of energy from the artist and often required him to make compromises, so it was his dream to henceforth paint only landscapes, as he confided to the art critic Johannes Widmer while walking home from his studio after seeing the lake: ‘I will also paint different landscapes than before, or at least the ones I have painted so far, differently. Do you see how everything over there dissolves into lines and space? Don’t you feel as if you were standing at the edge of the earth, communing freely with space? That’s what I’ll paint from now on. [...] In any case, I will only paint pictures of my own accord, no more commissions. Landscapes like these, planetary landscapes!’ [3] The term ‘planetary’ aptly describes the essence of this series of works: they are an expression of an allegorical vision of nature that transcends its concrete topographical appearance. Alberto Giacometti, who held Hodler in high regard since his youth, seems to have felt the same way, saying once: ‘It is as if these landscapes were made by someone who stands outside this world.’ [4]

In Hodler’s work, colour and form serve a pictorial order that allegorically represents the laws of nature. ‘Formes en rythmes, order enhanced by colour.’ Hodler noted in a sketchbook. [5] His contemporaries already considered Hodler to be a painter to whom colour was subordinate to form. However, in his later work, Hodler increasingly detached himself from the local colours associated with the forms and found his way to a freer use of colouring. He formulated this development in the following manner to Johannes Widmer: ‘I have neglected colour and put it aside for the ideas that I devoted myself to for years: to form, to line, to composition. [...] And now I have both, and more than ever colour not only accompanies form, but form lives, curves through colour. And now it is glorious. Now I have the large spaces.’ [6]

Paul Müller

[1] Johannes Widmer, Von Hodlers letztem Lebensjahr, Zurich: Rascher & Cie. Verlag, 1919, p. 45.

[2] Carl Albert Loosli, Ferdinand Hodler. Leben, Werk und Nachlass, Bern: Suter, vol. 4, pp. 214-215.

[3] Johannes Widmer, Von Hodlers letztem Lebensjahr, Zurich: Rascher & Cie. Verlag, 1919, pp. 8-9.

[4] Quoted from René Wehrli, Report of the Gottfried Keller Foundation 1963-1965, pp. 71f.

[5] Carl Albert Loosli, Ferdinand Hodler. Leben, Werk und Nachlass, Bern: Suter, vol. 4, p. 214.

[6] Johannes Widmer, Von Hodlers letztem Lebensjahr, Zurich: Rascher & Cie. Verlag, 1919, p. 43.

Hodler had moved into the apartment at 29 Quai de Mont-Blanc in December 1913. The panorama from there – with the ‘petit lac’ end of Lake Geneva, the Mont Salève and the distant Mont Blanc range – had already been captured by the artist in 1914 in a few paintings, in which the striking horizontal line of the row of houses on the opposite bank is overlapped by the summit of Geneva's ‘local’ mountain and, in some versions, the shoreline is populated by a series of rhythmically grouped swans. In the last series of works, to which this picture belongs, Hodler largely avoided anecdotal details or any references to civilisation.

The view was painted early in the morning before sunrise, as in eleven other versions. The remaining seven works, painted in the afternoon, are dominated by colder shades of blue. The pictorial field of the present view, tuned to a complementary blue-yellow chord, is divided horizontally into several zones, with the line of the mountain range dividing the composition in two. Above the strip of shore, painted in brown and white, the bright blue shades of the lake's surface are awakened by the yellow reflection of the morning light. The opposite bank is marked by a darker strip of trees and houses hidden by the morning fog. Above it extends the mountain range, delineated by the artist with a dark brushstroke, the blue tones of which contrast with the intense yellow of the morning sky. The horizon is marked by the triangle of the Môle mountain on the left, the broad Mont Blanc massif and, on the right, the nearby Petit Salève. Towards the upper edge of the picture, the yellow fades into light pastel shades.

Hodler often used the so-called Dürer disc to precisely transfer the contour of a model and, in isolated cases, of a landscape. Observing the landscape from his apartment, the artist seems to have used the window itself as a kind of Dürer disc, as Johannes Widmer writes: ‘For these pictures, he created diagrams across the entire width of the window of his room, painted in blue and red oil lines, which sharply reproduced the various silhouettes of the lake and mountains. These contours provided the framework for the landscapes, which were painted broadly and fluidly.’ [1]

Repeated forms, symmetries and parallels are compositional devices within Hodler’s theory of ‘parallelism’. According to the artist, they are an expression of the structural laws of nature, to which animate – including human – and inanimate matter are equally subject. Hodler’s view of the tendency of all objects towards the horizontal as a law of nature is also linked to death as human destiny (think, for example, of the series of works featuring the dying Valentine Godé-Darel): ‘Tous les objets ont une tendance à l’horizontale, à s’aplanir sur la terre, comme l’eau, en cherchant une base toujours plus étendue. La montagne s’abaisse, s’arrondit par les siècles jusqu’à ce qu’elle soit plane comme la surface de l’eau. L’eau va de plus en plus vers le centre de la terre, ainsi que tous les corps.’ [2] In this sense, Hodler’s last paintings are not mere snippets of a specific landscape, but represent allegorically a timeless law of nature.

The large symbolist figure paintings and portrait commissions of recent years had demanded a great deal of energy from the artist and often required him to make compromises, so it was his dream to henceforth paint only landscapes, as he confided to the art critic Johannes Widmer while walking home from his studio after seeing the lake: ‘I will also paint different landscapes than before, or at least the ones I have painted so far, differently. Do you see how everything over there dissolves into lines and space? Don’t you feel as if you were standing at the edge of the earth, communing freely with space? That’s what I’ll paint from now on. [...] In any case, I will only paint pictures of my own accord, no more commissions. Landscapes like these, planetary landscapes!’ [3] The term ‘planetary’ aptly describes the essence of this series of works: they are an expression of an allegorical vision of nature that transcends its concrete topographical appearance. Alberto Giacometti, who held Hodler in high regard since his youth, seems to have felt the same way, saying once: ‘It is as if these landscapes were made by someone who stands outside this world.’ [4]

In Hodler’s work, colour and form serve a pictorial order that allegorically represents the laws of nature. ‘Formes en rythmes, order enhanced by colour.’ Hodler noted in a sketchbook. [5] His contemporaries already considered Hodler to be a painter to whom colour was subordinate to form. However, in his later work, Hodler increasingly detached himself from the local colours associated with the forms and found his way to a freer use of colouring. He formulated this development in the following manner to Johannes Widmer: ‘I have neglected colour and put it aside for the ideas that I devoted myself to for years: to form, to line, to composition. [...] And now I have both, and more than ever colour not only accompanies form, but form lives, curves through colour. And now it is glorious. Now I have the large spaces.’ [6]

Paul Müller

[1] Johannes Widmer, Von Hodlers letztem Lebensjahr, Zurich: Rascher & Cie. Verlag, 1919, p. 45.

[2] Carl Albert Loosli, Ferdinand Hodler. Leben, Werk und Nachlass, Bern: Suter, vol. 4, pp. 214-215.

[3] Johannes Widmer, Von Hodlers letztem Lebensjahr, Zurich: Rascher & Cie. Verlag, 1919, pp. 8-9.

[4] Quoted from René Wehrli, Report of the Gottfried Keller Foundation 1963-1965, pp. 71f.

[5] Carl Albert Loosli, Ferdinand Hodler. Leben, Werk und Nachlass, Bern: Suter, vol. 4, p. 214.

[6] Johannes Widmer, Von Hodlers letztem Lebensjahr, Zurich: Rascher & Cie. Verlag, 1919, p. 43.

CHF 4 000 000 / 6 000 000 | (€ 4 123 710 / 6 185 570)

以瑞士法郎銷售 CHF 6 400 000 (落槌價)

所有信息随时可能更改。